Project Perchlorate - Exeter iGEM 2018

TL;DR

In the summer between my 2nd and 3rd years at Exeter, I took part in an internatational synthetic biology competition called iGEM (international Genetically Engineered Machines). This annual competition pits university (and some high school) teams against each other as they try to make the world a better place using genetic engineering. Along with 10 other students, shown below, I helped conceptualise, design and test a bioreactor capable of turning the chemical perchlorate found in Martian soil into breathable oxygen. I also helped design and make a couple of pages on the Exeter iGEM 2018 website and designed and created the logo you see on the right (or above if on mobile).

In the summer between my 2nd and 3rd years at Exeter, I took part in an internatational synthetic biology competition called iGEM (international Genetically Engineered Machines). This annual competition pits university (and some high school) teams against each other as they try to make the world a better place using genetic engineering. Along with 10 other students, shown below, I helped conceptualise, design and test a bioreactor capable of turning the chemical perchlorate found in Martian soil into breathable oxygen. I also helped design and make a couple of pages on the Exeter iGEM 2018 website and designed and created the logo you see on the right (or above if on mobile).

Motivation

Do I need more motivation to go to Mars than just that it would be awesome? Well, I’ll give you some anyway. It is human nature to be curious. We were driven to walk on the Moon and that same drive pushes us today to test humankind’s limits and step foot on another planet. Mars is the obvious candidate for a first attempt. It’s close, solid, and doesn’t have an atmosphere which will corrode your space-craft. It’s only a matter of time before we get there. The question now is: what do we do once we get there? Well, anybody who arrives on Mars will probably need to breathe oxygen. Unfortunately there isn’t a whole lot of that on Mars and every gram counts when launching a rocket so bringing tanks of it with us is less than ideal. Whether we’re there for exploration, science or because we’ve already destroyed our beautiful home planet, we’ll need to find a way of generating oxygen if we’re to survive very long.

Solution

Martian soil (more formally known as regolith) contains an abundance of a chemical called perchlorate. This is toxic to humans and therefore would need to be removed from any soil destined for agriculture. Perchlorate can also be reduced into oxygen using a two-step reaction via chlorite as seen below:

\[\text{ClO}_4^-+2\text{AH}_2\xrightarrow{\text{PcrABCD}}\text{ClO}_2^-+2\text{H}_2\text{O}\]Reduction of perchlorate into chlorite.

\[\text{ClO}_2^-\xrightarrow{\text{Cld}}\text{Cl}^-+\text{O}_2\]Reduction of chlorite into oxygen.

This it really very convenient! We can design a bioreactor with two-fold applications.

- It can remove toxic perchlorate from Martian soil

- It can break down that perchlorate into breatheable oxygen

Now all we have to do is design it.

Bioreactor

The full design process for this bioreactor is documented here.

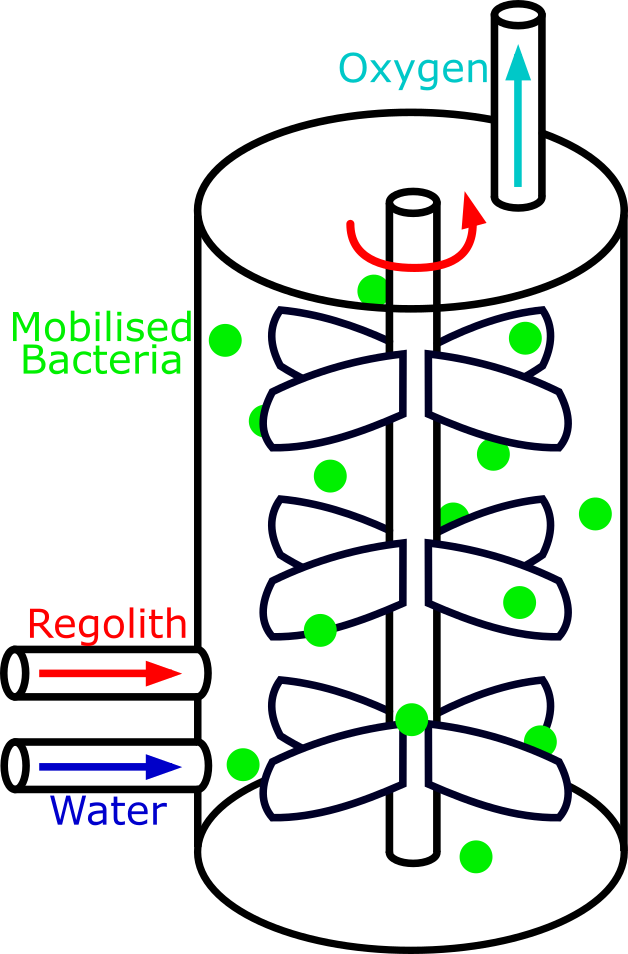

Initial designs

The iGEM Leiden 2016 team’s project was similar to ours, and so we took inspiration from their work. Our first bioreactor design shown above was along the same lines as Leiden 2016’s. It was very simple design, shown above, with mobilised bacteria being mixed with perchlorate in a single chamber. However, it was only a starting point.

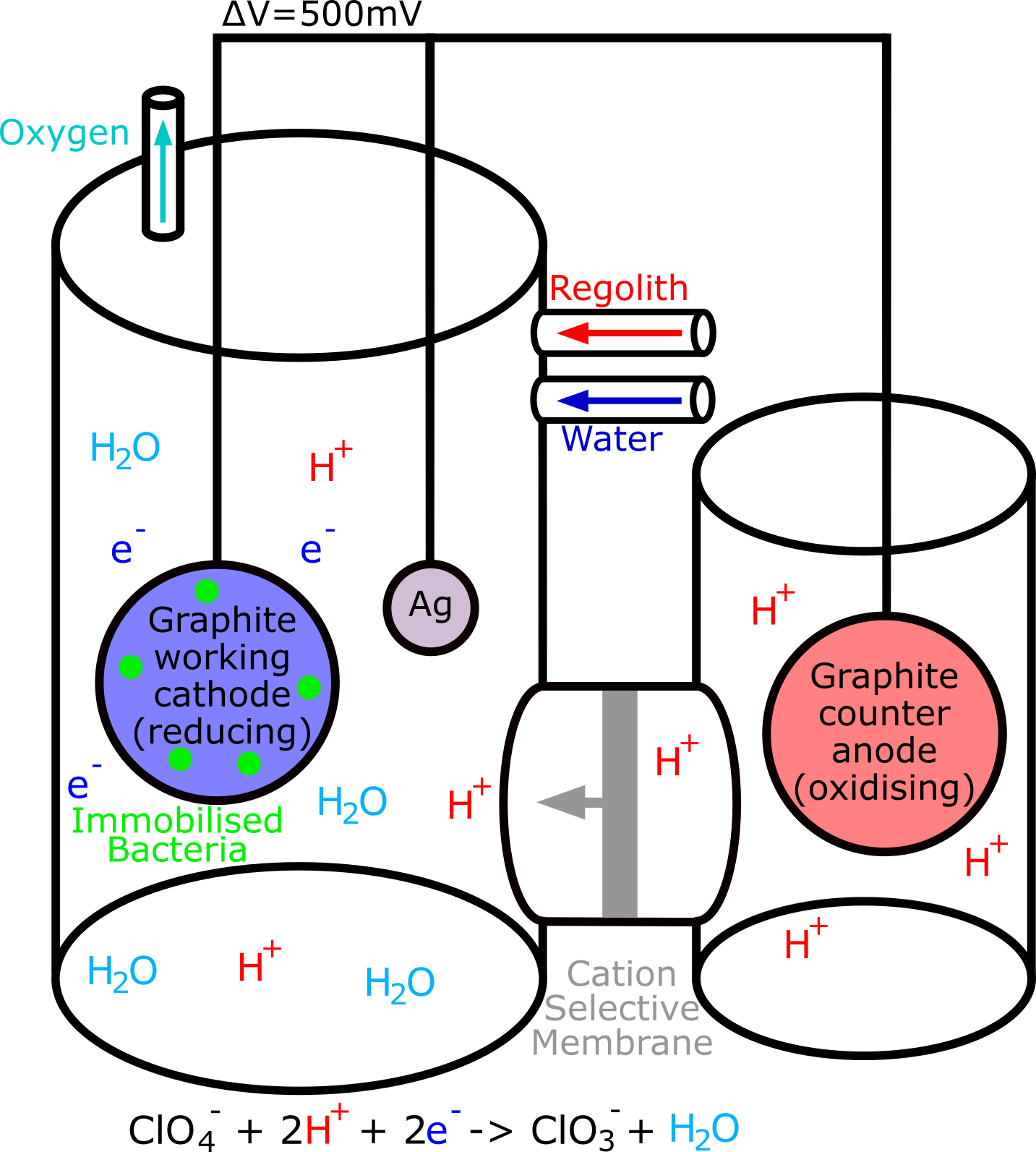

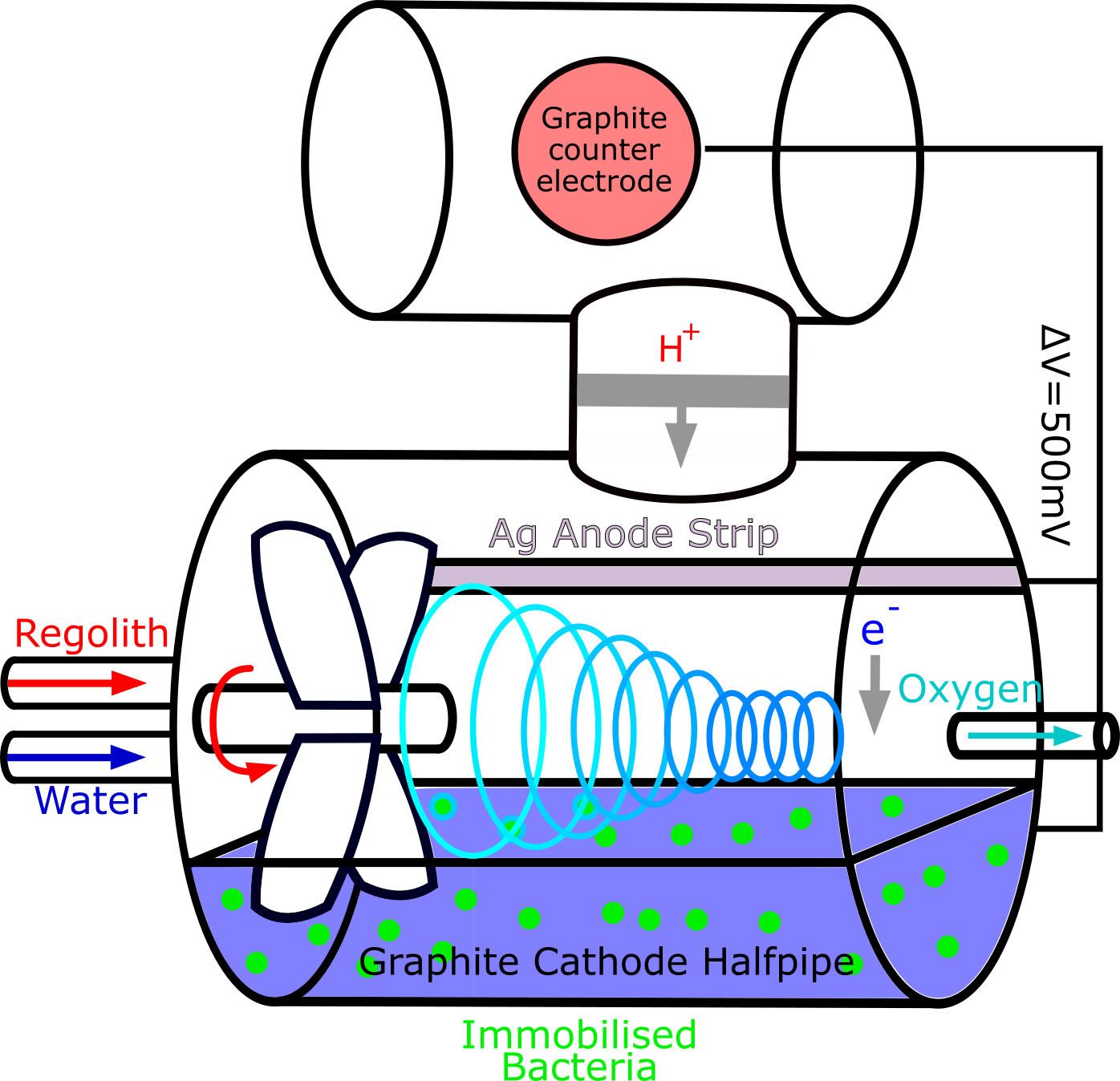

Specialists in DPRB (disperate perchlorate reducing bacteria), John D Coates and Ouwei Wang had drawn up loose designs for bioreactors using their research, shown above. In their design, hydrogen atoms would pass from an anode to a cathode through a cation selective membrane, aiding the reaction in the diagram below. This would speed up the conversion of perchlorate to chlorite, a rate limiting step. The design also switched to immobilised bacteria which reduces the chances of E. coli escaping.

From them we got the idea of using a cathode system to aid perchlorate reduction. After contacting them, we also gained insight into the different parts we needed to insert into our chassis, and the existing parts of E. coli that could be harnessed. They had been working on disparate perchlorate reducing bacteria, and offered a lot of input on how to apply their research to synthetic biology, bringing up the idea of bioreactors for bioremediation on Earth and on Mars.

Dr Clive Butler helped us to understand the needs and properties of bacteria that reduce compounds. From him we realised that we would have to supply haemin, molybdenum, and iron sulphate to our E. coli as the enzymes that reduce perchlorate are metalloenzymes.

Swirl-flow bioreactor

After we had decided that our bioreactor would be designed for Martian use, we spoke again with Professor Mike Allen. He introduced us to the concept of Swirl Flow Bioreactors (SFB), which would allow us to mix the perchlorate with the E. coli and separate the oxygen, all in one chamber. We took the design of a typical swirl flow bioreactor and adapted it to fit our needs of having immobilized E. coli and a cathode, shown above.

However, as Professor Allen pointed out, having an electric current in the bioreactor would provide opportunity for unexpected and unwanted reactions, while not contributing significantly to the rate of reaction. Therefore it was decided that the design should be simplified and the cathode removed. He introduced the concept of alginate beads for containing the E. coli to us. Plymouth Marine Laboratory were kind enough to lend us one of their Swirl Flow bioreactors, which we used to test whether the beads would be suitable.

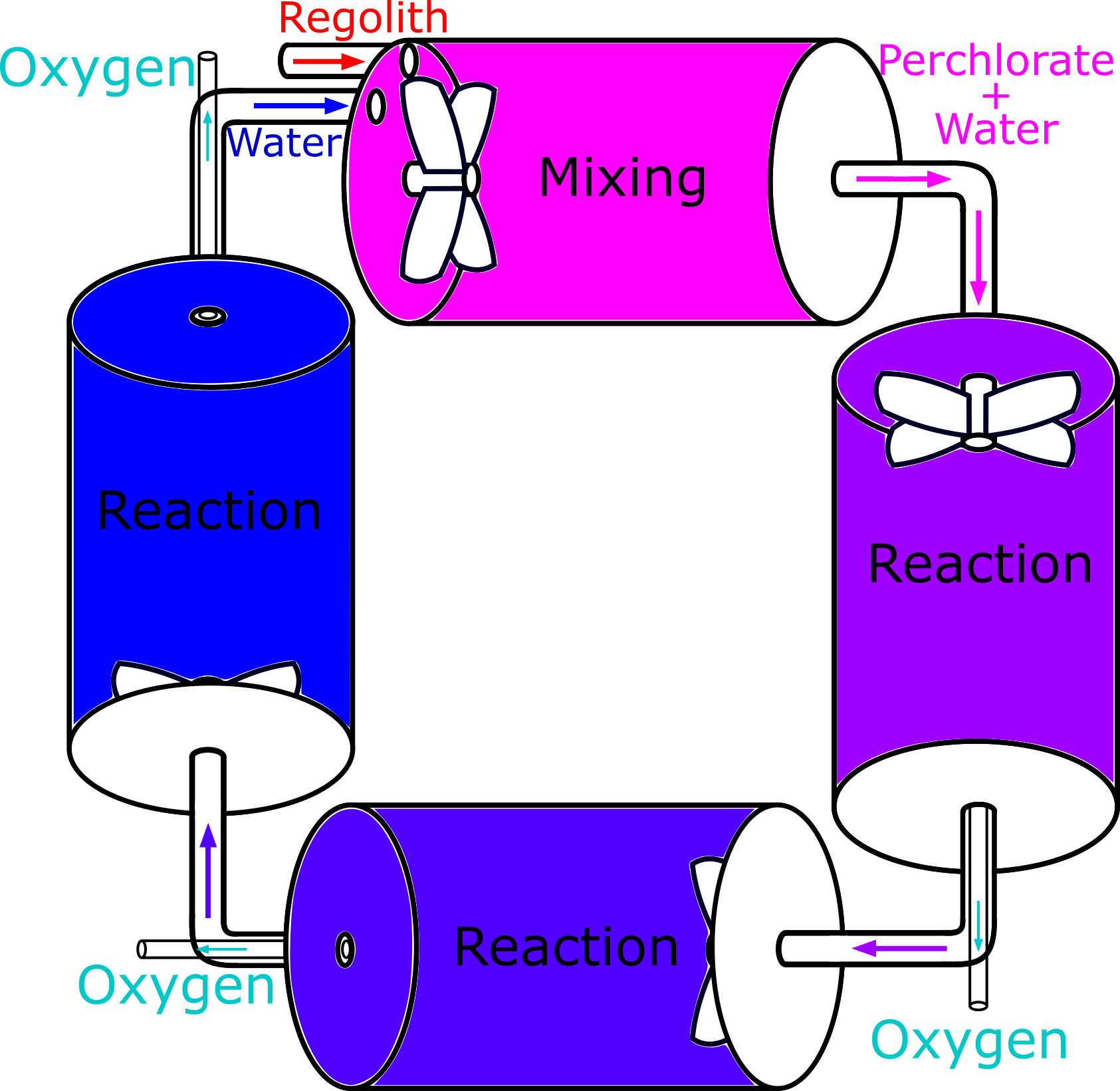

Our first SFB without cathodes involved four chambers, one to mix the regolith with water to extract the perchlorate, and three to consecutively reduce the perchlorate into oxygen until none is left. It is shown above. However, this had high energy requirements due to four impellers being powered at once, and could be simplified further.

Designing for Mars

With a solid base, we began to tweak the design based on the needs of a bioreactor on Mars, with the help of our stakeholders. We determined the most important aspects of a Martian bioreactor:

- 3D printable and light. This is due to limitations on what we could take to the planet. Michael Curtis-Rowse informed us that our procedures on Mars could be automated and that no human interaction with the bioreactor should be required. He helped determine the kind of materials we would have to make the bioreactor out of (printable plastic, Ultem, shown above).

- Resource efficient. Power consumption has to be low, in order not to drain the resources of the rest of the biodome. By reducing the bioreactor to one chamber and one impeller, it is possible to drastically reduce the energy requirements, since that is the main use of power.

- Shielded from radiation. Without protection, our bacteria will die on the Martian surface. The shielding also needs to be light enough to take to Mars. High Z Steel-Steel Composite Metal Foam (HZ S-S CMF) can block UV rays and neutrinos as well as pure lead (Shuo Chen et. al., 2015), while being much lighter and environmentally friendly.

- Safe. There must be a way to kill the bacteria in the bioreactor in the case of unwanted mutations or other unforeseen events. Fortunately, in the event of escape, the UV on the surface would kill any bacteria which made it out of the bioreactor. In the case of unwanted mutation, running copper-alginate beads through the bioreactor has been shown to kill E. coli (Simon F. Thomas et. al., 2014).

It was at this point we started thinking about integrating our bioreactor into systems that might exist in the future. We spoke to Melanie Pickett from NASA about their existing life support system, and how we could fit our bioreactor in with it. She highlighted the importance of protocols for disposing of old bacteria, and got us thinking about methods of regenerating the alginate beads as well as our water to soil ratio. We also spoke briefly to Professor Claude Gilles Dussap from the ESA about their life support system, Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative programme (MELiSSA). When talking to these companies, they specifically requested a Computer Assisted Design (CAD) image in order to fully understand our developments so far, which we generated as shown below.

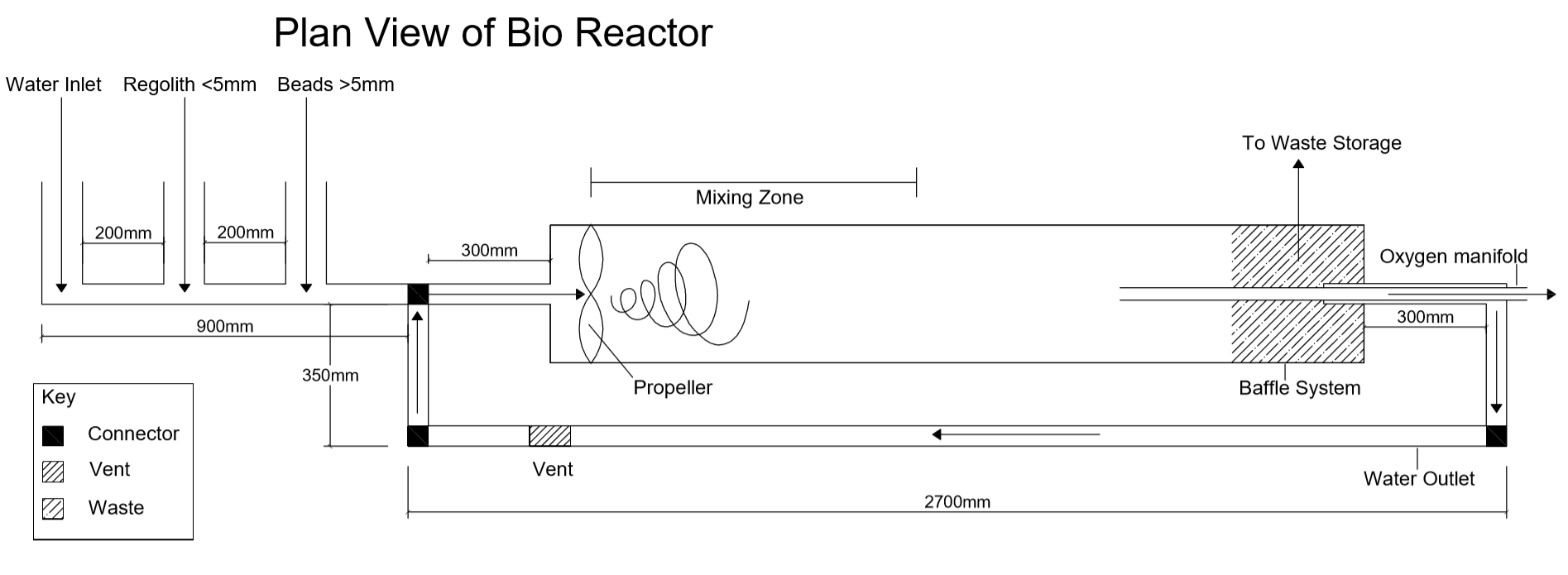

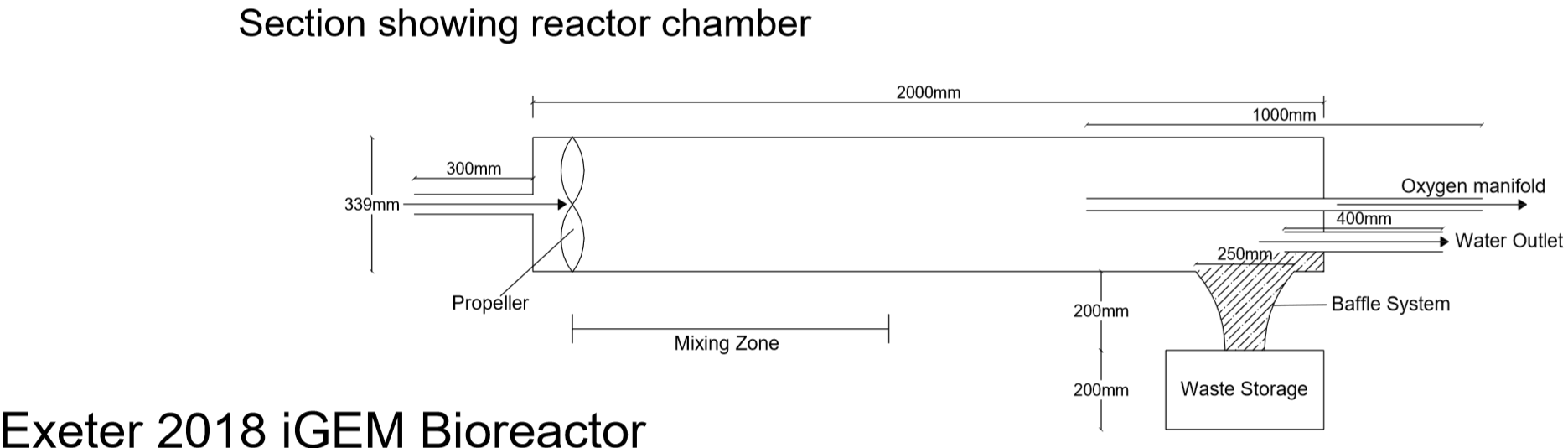

The final design

After talking closely with stakeholders throughout the entire design process, we settled on a final design. The design features a single impeller chamber in which the reaction will take place. On the Martian surface, a rover would shovel regolith into the bioreactor with water. Then a filter would remove the solids rocks and soil, leaving only a perchlorate solution. This solution would then flow into the reaction chamber with alginate beads containing E.coli, where the perchlorate will react with the bacteria. The filtered soil will be deposited into the baffle system by the vortex, since it will be the most dense material, and then removed. Oxygen produced by the reaction will be the least dense, and so the vortex will concentrate it in the centre of the chamber, to be carried out via a manifold. The remaining water will be recycled back into the chamber for the next reaction. It is a simple but efficient design.

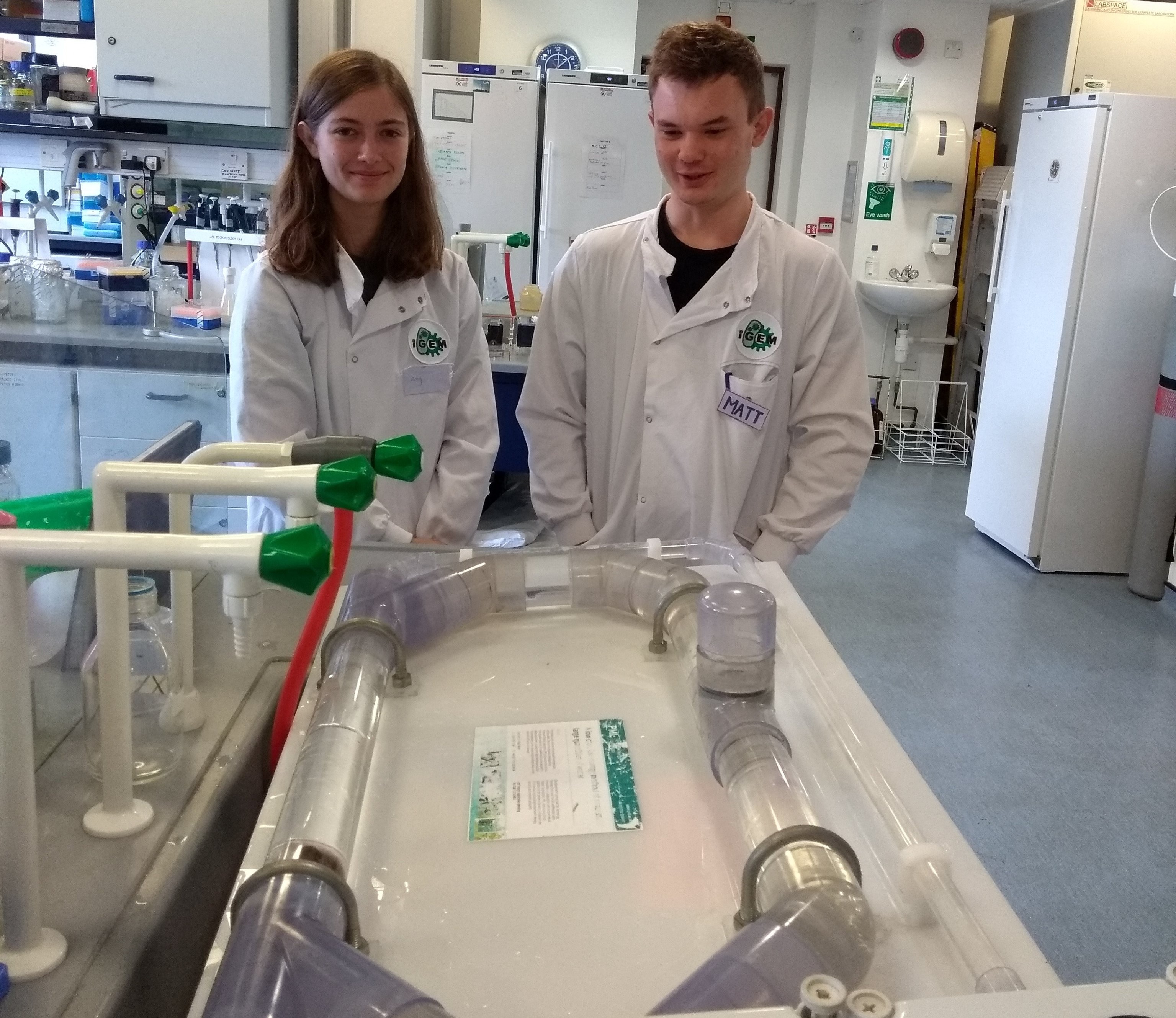

If we had had more time, it would be valuable to build and test a prototype, however, we were lucky enough to experiment with an existing, similar bioreactor which gave us an idea of how our design would work. We also took this to the Giant Jamboree in Boston where we demonstrated it working with the use of glitter to represent the perchlorate and bacteria circulating the bioreactor as intended. Below is an image of me (left) and Matt, another member of the team, working on the bioreactor in the lab.

Awards

At the end of the competition, our team was awarded a gold medal at the Giant Jamboree. If interested, you can read about how we qualified for this award here.