Searches for Gravitational Waves from Known Pulsars at Two Harmonics in the Second and Third LIGO-Virgo Observing Runs

Below I will describe in brief the main points of the paper published here. Please see the paper for full details, as here I will focus on the parts of the paper which I personally was involved in.

LIGO Science Summary (first draft written by me, with improvements thanks to others in the collaboration).

Gravitational waves from pulsars

In order for an object to emit gravitational radiation, it needs to have some mass asymmetry. Imagine a frictionless rod submerged in water. If you rotate the rod about its long axis, you would not observe any waves. This is because it is rotationally symmetric. If you rotate the rod along another axis, however, you would expect to see waves. Similar to this, a mass with some acceleration will create waves in space-time. Pulsars are hypothesised to have some ellipticity, also referred to as “mountains” which can be caused at “birth” or during their lifetimes through processes such as accretion. Unlike Earth’s mountains they are merely a few centimetres tall, but even that is enough to have an effect noticable on Earth.

As a pulsar rotates with this ellipticity, the emission of gravitational waves (GWs) will cause it to lose energy in the form of angular momentum loss. The amplitude of the GW emitted scales with increasing frequency so the high frequencies of pulsars mean puts the GWs within current detector sensitivity ranges. Although no such signal has been directly observed yet, naive upper limits on the GW amplitude can be placed by assuming that all rotation energy that is lost by the star is lost through the emission of GWs (this is unlikely as a large fraction is expected to be lost through magnetic dipole radiation). We call these limits “spin-down limits”.

The frequency of the GWs are also expected to be closely linked to the pulsar rotation frequency so that the GW frequency is 2x the pulsar frequency. There are some processes which can also cause emission at 1x the frequency such as free precession of the pulsar or a independently rotating superconducting core. In order to account for these possibilities, searches look for GW signals at both 1 and 2 times the pulsar rotation frequency.

Why care?

Unfortunately, due to their incredibly small size, pulsars are difficult to observe directly. Often, we don’t know much more about them than their distance and rotation frequency. This means there are still many questions about pulsars which we haven’t yet answered. For example, there are various possible theorised equations of state (EoS) for pulsars which each give different upper limits on the maximum deformation (ellipticity) allowed. So, measuring deformation through GW observation would help constrain the EoS.

Additionally, there are other processes which may emit gravitational waves which occur beneath the crust of the star. For example, r-waves or Rossby waves are a phenomenon which occur on Earth and are similarly predicted to occur on pulsars, but have yet to be proven. An observation of a GW from one of these processes would provide strong evidence of their existance and give valuable information on the proccesses beneath pulsar crusts.

This search

Now I hope you can see why it might be a good idea to look for these GW signals, and that is exactly what we did. We looked at data from the O2 and O3 (meaning second and third) observing runs of LIGO-Virgo in what is an updated version of a search performed on O1 and O2 data previously. There are various types of searches. A targeted search will look for gravitational waves from known pulsars. Since we know their distance and frequency for example already, there are fewer parameters which need to be searched over, leading to a less computationally expensive and more sensitive search than other methods. For example, an all-sky search looks for signals over a wide range of parameters in all sky directions while directed searches look for signals in small sky regions where it is believed likely for a pulsar to exist.

GWs from 236 pulsars were searched for, with 74 of these pulsars having not been included in the previous search using O1 and O2 data. 168 of these pulsars are in binary systems and 161 pulsars are millisecond pulsars. Time domain Bayesian analysis was performed on all pulsars searching for signals at 2x and both 1x and 2x the rotation frequency. In the absence of a detection, we present 95% confidence upper limits for the GW amplitude or “strain”.

Results

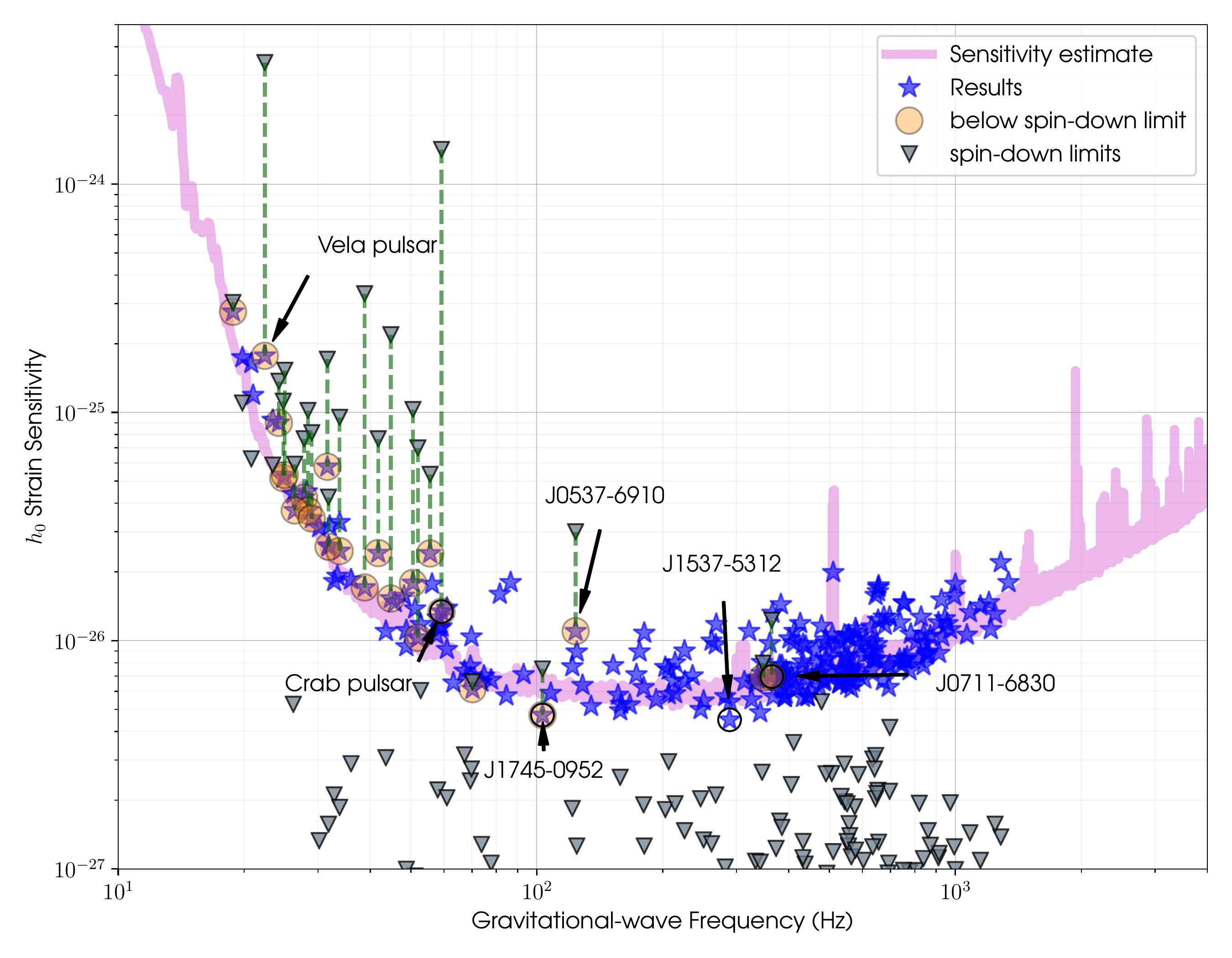

The image above shows the main results of the paper. On the y-axis we have \(h_0\) which represents the strain sentisivity, or gravitational wave amplitude. On the x-axis is the frequency of the gravitational wave, which in this case is twice the frequency of the pulsar. The blue stars represent the 95% confidence upper limits on GW amplitude, \(h_0^{95\%}\), for each pulsar produced in this study. The spin-down limits for each pulsar are also shown as grey triangles, and where the upper limit surpasses (is lower than) the spin-down limit, the result is circled in yellow. Finally, the sensitivity estimate for the detectors is overlayed in pink.

There were 23 pulsars which surpassed their spin-down limits, which means that for those pulsars we can place new upper limits of quantities such as mass quadrupole and ellipticity. For example, for the Crab pulsar (see labelled on the graph), the upper limit as a fraction of the spin-down limit is only 0.0094, meaning that less than 0.009% of its angular momentum loss can be attributed to GW emission. This corresponds to a maximum ellipticity of \(7.2\times10^{-6}\).

My role

I performed the Bayesian analysis search for GWs at both 1 and 2 times the pulsar rotation frequency. I performed seperate analyses for pulsars which experienced glitches (sudden temporary changes in frequency) and for pulsars which had sufficient information from observation to allow for restricted (narrow) priors on inclination and polarisation angles (rather than the default flat prior). Also, for pulsars who did not have EM observations during the entirety of O2, analyses were run using just O3 GW data. Finally, I lead the writing of the paper, with the exception of sections about F-/G-/D- statistic and 5n-vector searches as they were performed by another group. Throughout the paper writing process, I had valuable help and input from a variety of collaboration members. Hence, the full collaboration authorship on the paper.

Other links

I presented this paper a number of times to the LVK and at a couple of conferences. Here are links to the presentations I have given:

- BritGrav 2022 (pdf)

- EAS 2022 (pdf)